As the global refugee crisis has become evermore politicized, we have turned a blind eye to the realities of the men, women, and children, stuck in impromptu refugee camps throughout the world. While the United Kingdom pays considerable sums to keep the refugees in Calais at bay, Australia has conceived a unique and highly criticized solution to the refugee crisis.

In 2001, the Conservative Australian and Nauruan governments reached a bilateral agreement forbiddingly labeled the “Pacific Solution”. It allowed Australia to set up an off-shore immigration detention center on the small Pacific Island of Nauru, 4,500 kilometers east of Australia, in return for economic aid amounting to $4 billion AUSD.

According to the Human Rights Watch, Nauru quickly became a “human rights catastrophe”.

However, after a landslide election in 2007, fought and won around the immigration issue, the new Labor leader Kevin Rudd dismantled the agreement. This respite was short-lived, and, in 2012, the “Pacific Solution” re-emerged under the title – “Operation Sovereign Borders”.

The Australian Navy routinely intercepts human smugglers carrying asylum seekers on overloaded and unseaworthy boats as they leave Indonesia. They are often turned back to Indonesia, many of them capsizing on the treacherous journey home, with hundreds of lives lost.

Others are picked up by the navy and placed in mandatory detention on Nauru where they face years of uncertainty and misery in a legal no-man’s land. According to the Australian Human Rights Commission, there are 543 asylum seekers, including 70 children, currently in detention in Nauru.

The controversial reopening of the Immigration Detention Centre has led to multiple reports of human rights abuses, including deprived living conditions, sexual and physical abuses, and the indefinite detention of adult and child asylum seekers.

The Australian Integrity Commission released a review in 2015 into allegations of sexual abuse that found reports of rape on women and children. Save the Children supports these claims of abuse, explaining that, “on occasions women have been forced to expose themselves to sexual exploitation for access to showers and other facilities”. In all, thirty-three asylum seekers have allegedly been sexually assaulted. Yet, no one – either refugee or Nauruan – has ever been charged.

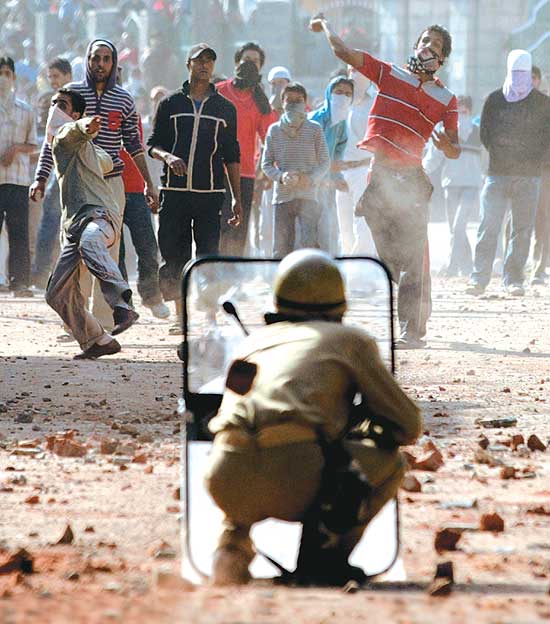

Such incidents often go unreported because of the victim’s concern that their complaint would harm their claims to asylum. In fact, it took two years for the first asylum seeker to reach refugee status, and many have remained in detention for up to seven years. This uncertainty has led to increases in frustration among the detainees, and various forms of protest have emerged. Hunger strikes, self-harm and riots have become commonplace.

An independent inquiry has also detailed a worrying amount of self-harm from 2013 onwards. Seventeen minors are recorded to have engaged in incidents ranging from an attempted hanging by a 16-year-old to children swallowing washing detergent. Australian Senator Hanson-Young testified that “children as young as eight years old have been involved in lip stitching”, as part of a growing protest movement.

The chief medical officer of the Australian Border Force, Dr. John Brayley, pronounced, “the scientific evidence is that detention affects the mental state of children, it’s deleterious…Wherever possible, children should not be in detention.”

Despite Nauru’s decision in 2014 to increase the price of their media visa from $183 USD to $7,328 USD, international reporting of the human rights abuses have gone undeterred. Demonstrations across Australia have also increased, as knowledge of the conditions on Nauru become widespread. On the 9th February, 6,000 protestors in Melbourne implored new Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Turnball to rethink Australia’s policy toward asylum seekers. The need for change is becoming evermore apparent.

Yet, the rhetoric employed by recent governments is that asylum seekers are criminals deserving of punishment and this is engrained within the minds of the vast majority of Australians. While the Premiers of Victoria, South Australia, Queensland and New South Wales have offered a glimmer of hope in their pledge to house Nauruan asylum seekers, the Federal Government’s policy of incarcerating asylum seekers remains resolute.