Amid the chaos from the Syrian Civil War as well as rising violence from Islamic State (IS) militants, millions of Syrians are being forced to flee their homes. Since the outbreak of the civil war in March 2011, over nine million Syrians have been uprooted. More than six million remain internally displaced, while an additional three million refugees have managed to flee to the neighbouring countries of Turkey, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon.

These nearby countries have undergone enormous strain to support the massive influx of refugees. Iraq, also embroiled with domestic chaos due to IS-led violence, has seen its own population fleeing the country. In Turkey, over a million Syrian refugees have officially entered the nation, which has come with substantial costs in the range of $1.5 billion, and increased anti-immigrant, anti-Arab and anti-Kurdish sentiments. Neither Jordan nor Lebanon have much control over the crisis overrunning their countries, which has led to domestic unrest. The problem is especially prominent in Lebanon, which has no formal refugee camps and little control over the inpouring of refugees across their long border with Syria. Overall, the refugee crisis has further deepened the already troubled region’s instability.

However, the refugee crisis faced by these countries has garnered only a limited response by most of the international community, to the consternation of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The major exceptions have been Germany and Sweden, who have both come out as leaders in this crisis. Germany has accepted most of the European Union’s (EU) 150,000 asylum settlers, and have pledged an additional 28,500 resettlement spots. Sweden, which has around one quarter the population of Canada, has taken in more than 30,000 Syrians by itself, and is calling on EU countries to support the crisis with more than funding.

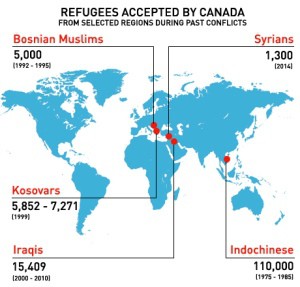

In comparison, the Canadian response to this crisis has been far less substantial. Last year, the government pledged to bring in 1,300 Syrian refugees – only 200 through government sponsorship and 1,100 through private sponsorship. When Chris Alexander, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, was asked about the problem during Question Period on October 6th, he stated that, “We have brought over 1,500 Syrians to Canada.” However, that statistic is widely questioned by refugee advocacy groups who argue that that number includes Syrians resettled prior to 2013. Independent estimates place the actual total number of resettled refugees since 2013 closer to 200.

Regardless of the actual numbers, there has been a sharp rise in the difficulty associated with bringing Syrian refugees to Canada. The problem, as argued in an internal government report released at the end of 2013, is a bureaucratic backlog inside the Department of Citizen and Immigration, caused by federal budget cuts. The Centralised Processing Office – Winnipeg (CPO-W), which handles privately sponsored refugee claims, was created in 2012, aiming to increase efficiency at a lower cost through the centralisation of numerous local and international offices.

However, this centralisation has in fact led to an unprecedented backlog which the report estimates will take, “…over 2 years to clear the existing inventory of cases, in addition to almost 2 ½ years to process projected 2014 application submissions.” The result has been that sponsors typically do not receive a case decision for nearly a year, although the current benchmark aims for sponsorship decisions to be made within 30 days of receiving the application.

The report recommended that the government hire more staff to cope with the backlog. While departmental officials have stated that efforts are being made to speed up the process, they have refused to state whether more staff have been hired since the report’s release.

The problem’s effects extend past the Syrian refugee crisis. The processing system is conducted according to priority, with Syrian refugees currently being moved to the top of the pile. So, while the backlog has been seriously impacting Syrian refugees, it is also further delaying immigration from other countries.

The UNHCR has been pressing Canada to take a larger role in the crisis, aiming to help them resettle 100,000 Syrians over the next two years. However, the Canadian government has been reluctant to respond to the request or publicly discuss refugee target numbers. This limited response is juxtaposed against Canada’s reputation for opening its borders to refugees in times of crisis, such as the 1979-1980 resettlement of over 50,000 Vietnamese.

While Canada has made generous financial donations, it is clear that there is more that the government could be doing, beginning with the immigration backlog. In light of such a massive crisis, Canada should step up domestically and help ensure an effective global response as they have done so often in the past.