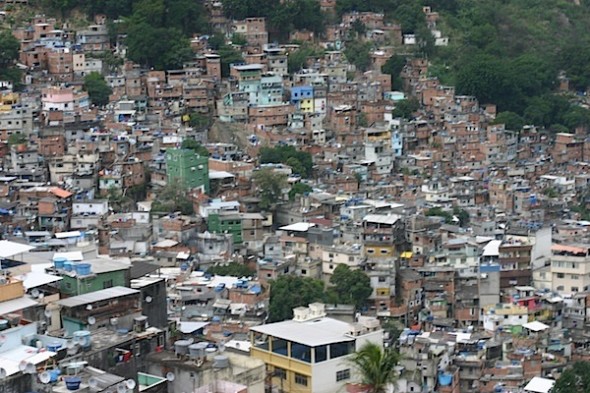

Police take-overs of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, or shantytowns, were at the forefront of news coverage in 2011 as Brazil began to prepare for upcoming events such as the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. The general goal is for the city to be “cleaned up” and this includes upgrading the favelas that line the city. Electricity, running water, police enforcement to remove drug and gang violence, as well as job opportunities are being brought into certain communities hoping to provide a needed face lift for these parts of Rio.

On the other hand, upgrading can also include evictions, or even destruction of these slums. For example Rio’s Vila Autodromo is set to be demolished in order for a new highway to be built in time for the 2016 Olympics. For this to happen thousands of people who have dug their roots into this community will have to be evicted. The government has plans to move the community to an apartment complex, however residents are resisting adamantly, claiming they have a right to remain in their homes, despite a lack of formal ownership of the land. In fact, the government owns the land even though the favela is legal by a 1994 government contract granting the settlement a 99-year land title. Many are now questioning the government’s right to seize this land.

Altair Guimares, 17-year resident of Villa Autodromo and president of the residence association, told TV news station, France24, “Our government wants to act like Robin Hood, but the other way around: take from the poor to give to the rich.” Also commenting on the issue of favela evictions is Christopher Gaffney, professor at Rio’s Fluminense Federal University, who told the NY Times that “These events [the World Cup and Olympics] were supposed to celebrate Brazil’s accomplishments, but the opposite is happening,” also adding “We’re seeing an insidious pattern of trampling on the rights of the poor and cost overruns that are a nightmare.”

Residents like Guimares are fighting hard to remain in their homes, even turning to Rio de Janeiro Federal University urban planners to find an alternative. They have taken the issue of eviction up in court in previous years, and have so far been able to dodge eviction. In the wake of 2016 Olympic preparations, the issue is being revisited and many have taken to protests in front of Rio’s city hall. The situation does not look promising for residents of communities like Vila Autodromo, as mayor Eduardo Paes (government official in charge of preparing his city for upcoming events) was re-elected this October and the plans continue.

Slum upgrading is not unique to Rio, as projects aimed at alleviating issues within slums exist essentially wherever there are slums. Complications with the project and those receiving it arise, as they are now in Rio, when upgrading conflicts in resident’s rights and projects in one way or another lead to people losing the place they call home. It is a wonder that residents find a home in slum communities, as living conditions can be very difficult. Lack of electricity, sewage, running water, proper home infrastructure, roads and the like, commonly characterize life in slums. This is the rhetoric that UN Habitat has taken up, believing that conditions in slums are in dire need of upgrading. The issue is with implementation and how the rights of slum dwellers are taken into account.

The difference between in-situ, or smaller scale, and standard upgrading is key. McGill PhD candidate, Cassandra Cotton, points out that when it comes to standard upgrading it is about “trying to bring slum dwellers into a formalized economy and a formalized city so there are benefits” but really success depends on the approach and “a lot of the standard programs haven’t been including the populations that they are dealing with”. Cassandra Cotton has done research in Korogocho, a slum in Nairobi, for her dissertation at McGill, with the African Population and Health Research center, helping to collect data to “bring policy into action”. The main goal of many organizations, including governments and UN Habitat, is to upgrade the lives of slum dwellers. It is necessary to realize, however, that although slum dwellers may not live in the best of conditions, they do have deep investments in their communities and the land they live on. Cassandra emphasizes this by saying: “If a quarter of the population has been living there since birth, you have people who have settled and have roots and have raised their children in these homes and they don’t necessarily like the quality of their housing but there are a lot of reasons why they do enjoy it and why it is important to them”.

In other words, Cassandra says, “People want access to transportation and access to clean water they just do not want to leave their homes”. Upgrading programs, like the one in Korogocho, are successful when they include the community they are trying to help in the planning and implementation. The motive to improve access to better health and living conditions must be there in first place. Cassandra concludes that programs need to be “focused more on improved standards of living, and it really is something everyone can get behind”. Moving back to South America, upgrading programs in Rio perhaps need to take a lesson from what has already been learned in Korogocho: a community focus proves successful too.