Environmental Racism against Indigenous people is an important issue to examine as it concerns not just the people within the communities but everyone around the world. The deliberate targeting of communities of Indigenous peoples and communities of color for toxic waste facilities, the official sanctioning of the presence of life threatening poisons and pollutants, and the history of exclusion of these individuals from leadership in the environment movement describes a racial discrimination that is known as environmental racism (Holifield, 2001, 83). If we for example, examine the case of environmental racism against the Chippewa People of Aamjiwnaag, we must also look at how this Indigenous community interprets and explains natural phenomena and the relationships that are part of their cultural understandings (Rice, 2005, 1).

Sarnia and Aamjiwnaag have the most toxic air in Canada due to levels of mercury and hydrogen sulfide levels. This is a prominent example of environmental inequality in Canada where the air pollution and water quality is hazardous on the Indigenous reserves. This is not only a human rights issue, but Canada yet again fails to recognize the connection Indigenous people have to their landscape that is inherently bound to their community and cultural practices (Environmental Law Centre, 2011, 2). Understanding how Indigenous communities experience environmental racism allowed me reflect on my own community as a woman of color who lived in India. Hence, this paper will explore how environmental programs can assist in decolonizing and relationship building strategies, reconciliation, and how I, as a settler, will incorporate the knowledge gained through my research in my future work.

Indigenizing Approaches

By examining the importance of interconnectedness with nature and how environmental destruction interrupts cultural practices of Indigenous people, we need to see why an indigenizing approach in this situation is important. Destruction towards the environment is not just an Indigenous issue but rather everyone’s concern as it effects the needs of the individual and their family in terms of physical health, poverty, unemployment, and mental health (McLachlin et al, Lecture, 2014). With the emphasis on technology, many people have forgotten their connections with the earth, where they fail to recognize other forms of knowledge critical to our survival (Rice, 2005, 31). Here, a discussion around the medicine wheel is required and how it applies to the environmental racism that Indigenous peoples and communities of color experience. The medicine wheel symbolizes the interconnection of life, the various cycles of nature, and how life represents a circular journey (Freeman, Lecture, 2014). The four points represent the balance between spiritual, mental, physical, and emotional aspects of health. It would be important to mention how environmental racisms affects people’s spirituality, mental, physical and emotional health. In working with Indigenous communities who are experiencing environmental racism, we need to be aware of how humans have damaged the environment and for what purposes. We need to address the impact this has had on indigenous communities with regards to land being taken away, destroyed, and being polluted to the point that it is not safe for the communities to live there. The problem is, in this age of globalization where technology is depended on advancing society, the value of the earth is being forgotten and how destroying it means the destruction of humans. This issue needs to be made aware to everyone. Starting in schools and universities would be a step in that direction. Knowledge on environmental destruction should be taught in all faculties rather than just the humanities and social sciences. One way to do this would be to have outdoor experiential learning programs from Indigenous perspectives that discuss the impact of environmental destruction on water, soil, and air systems (McLean, 2013, 356). Involving children and university students is important because they often initiate movements that can impact policies. Raising the consciousness of students in all faculties would challenge the technological age, which is at the expense of the earth. Students would be encouraged to reconnect with nature, land, and enjoy its beauties while learning how it impacts their mental and physical health. Hence, in working with indigenous communities who have experienced the destruction of their environment, I would consult with them about involving youth in a project such as this and how they feel bringing light to this issue would impact the policy makers’ and developers’ mind. In doing this work, however, I would have to be mindful about who has access to resources. Environmental education tends to be dominated by white middle and upper class families who have the means to access education and sometimes lack a connection to how environmental destruction is linked to social and political issues (McLean, 2013, 357). Hence, why it is extremely important for us to decolonize and create relationship-building strategies.

Decolonizing and Relationship Building Strategies

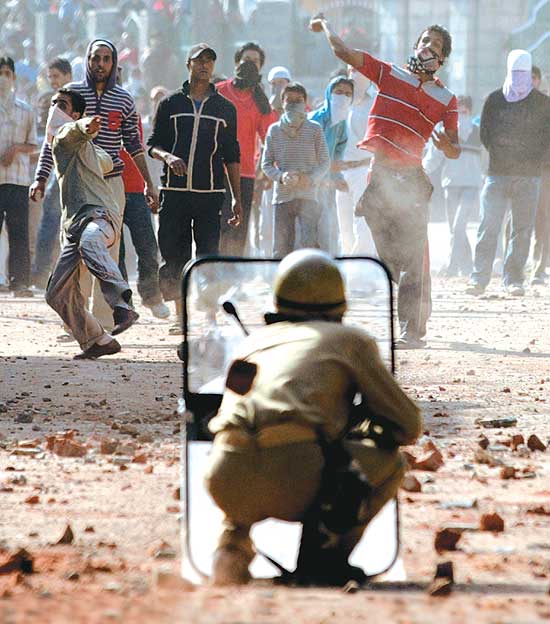

In order to decolonize, we need to address that environmental racism exists. This occurs not only in Indigenous communities in Canada but all around the world. Due to overexploitation of resources in places such as India, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, there is a shortage in “sources” of raw materials/ natural resources and a lack of sufficient “sinks” to absorb wastes from industrial pollution, which is causing harm to the environment (Magdoff, 2013, 64). In some areas in Africa, mining still utilizes child labor; now although there is an ongoing awareness about the issue, it is often hidden in areas where resources are being exploited. The West uses its power to highlight this in some areas however it is a hoax that allows them to go into the country to exploit the resources and assimilate the people to adopt their ideologies of democracy (Munt, 1994, 49). Environmental destruction and exploitation of resources are not considered important when it benefits the corporations. The exploitation of the Canadian tar sands is an example of high prices for oil that is both costly and ecologically damaging (Magdoff, 2013, 64). We need to understand that environmental issues greatly affect indigenous communities as well as non-indigenous communities, which is evident with the high rates of cancers, diseases, fertility issues, etc.

The first step towards decolonization is to address environmental racism and be accountable for our actions. Industries and governments that support policies or developments that contribute to environmental destruction needs to be addressed. Issues such as land rights, local water, and transportation systems, land- based cultural identity, and land use planning are basic human rights of everyone (Zapf, 2009, 79). Government must collaborate with indigenous groups to create strategies in ways that can help preserve resources and keep our environment healthy.

On a micro level, experiential land-based learning programs that discuss environmental racism are important for decolonization. Environmental education currently lacks a critical race analysis and generally does not include a history of colonial violence or political analysis of the destruction of environment. For decolonization and relationship building, it would be important for environmental education to be created from an Indigenous framework, which discusses environmental racism in Canada and around the world (McLean, 2013 357). Currently, education related to the destruction of environment examines a world within a post-racial context; this has to be challenged since we do not discuss sustainability or talk about what areas face the most environmental degradation. In academia, environmental destruction is looked at from a scientific perspective; this needs to change, since the environment impacts people’s physical and mental health, body, and spirituality. The mainstream approach to the environment has a narrow view of what constitutes the environment and therefore excludes input by marginalized people (Kapoor, 2000, 269). It is also important to look at how the physical environment impacts an individual’s or community’s social environment. Harm to the physical environment can impact a person’s body where they might get sick. This in turn can affect their social environment as they might have trouble accessing resources or have trouble with their family in coping with their health. It could also have an effect in employment if you are unable to get to work due to your health. Hence, when decolonizing and building relationships, understanding that environment is connected to multiple aspects of a person’s life is critical.

Reconciliation and Alliance Building

In the Canadian context, reconciliation and alliance building would be in the form of providing Indigenous people their lands back as well as clean drinking water, which is a human right. Industries must be accountable for their toxic waste by providing funding for initiatives that can clean up our air and help in the purification of water systems. It would mean to recognize Indigenous practices such as farming and self-sustenance. It would mean actually listening to Indigenous people and learning from them. Stigma, stereotypes, and generalization must also be ended. Indigenous peoples’ cultural practices and the fact that they are distinct from “traditional” western culture also need to be recognized (Freeman, Lecture, 2014). Reconciliation would also mean avoiding tokenism by taking initiatives to do the learning yourself and not expecting Indigenous communities to do the teaching. This would mean learning about how environmental racism connects to dispossession, violence, and Indigenous-Settler relationships, while offering opportunities for Indigenous counter narratives (Freeman, Lecture, 2014). Alliance building would also mean recognizing how environmental racism makes us aware of ourselves through our class, race, age, values, and assumptions. It would allow us question power structures, dynamics, and the roles we take on and the implications it has on people who are directly impacted by what is happening in their environment.

My Experience and Connection

Back in 2000, when I was 8 years old, I lived in India with my grandparents in a community that experienced environmental racism. My house was right next to the international airport where my grandfather helped in the repair of airplanes. Near the house, there was a large piece of land where goat herders and cows would come and enrich the soil to grow local fruits and vegetables. In 2000, a western airline deliberately threw waste from its airplane onto that large piece of land below. The community contacted the government and the airplane company was reprimanded and ordered to a clean up. However, what was heartbreaking was that even with the clean up, that area was never returned to its initial state. The goats and cows stopped coming and it became a piece of land that was used for shopping malls. This example taught me a valuable lesson about accountability and the loss that comes to communities through environmental racism.

For Indigenous communities, even if they are reprimanded a piece of land or if industries are held accountable, the loss of their land or those of loved ones impacted by pollution through cancer or other diseases can affect their own mental health. So, in my future work practice, I hope to validate this loss. For many people, going through the loss is important whereas for others healing from it is. I hope that I am transparent in addressing how this is difficult based on the relation that land has with Indigenous people and support them in the best way I can.

I hope to continue to be an ally who listens rather than takes up space and continues to engage in social justice to bring awareness to environmental racism and destruction and how it affects more than just our physical environment but rather all aspects of our lives. I hope that I, as an immigrant settler, decolonize and pass on this knowledge to my family and friends who can also join me in working towards this issue. I also hope I am able to incorporate Indigenous knowledge and environment in the work that I do currently and in the future.

References

Environmental Law Centre. (2011). Environmental Rights: Human Rights and Pollution

in Sarnia’s Chemical Valley. Victoria, BC: Author.

Freeman, B. (September 18, 2014). Concepts and Process of Indigenization in

Contemporary Social Work. Conducted from McMaster University, Hamilton, ON

Holifield, R. (2001). Defining environmental justice and environmental racism. Urban

Geography, 22(1), 78-90.

Kapoor, I. (2001). Towards participatory environmental management?. Journal of

environmental management, 63(3), 269-279.

Magdoff, F. (2013). Global Resource Depletion: Is Population the Problem?. Monthly

Review, 64(8), 13-28.

McLachlin, M, Crump, A, Sindchakis, M, C. (November 20, 2014). Environmental

Racism Against the Chippewa People of Aamjiwnaag. Conducted from McMaster University, Hamilton, ON

McLean, S. (2013). The whiteness of green: Racialization and environmental education.

The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 57(3), 354-362.

Munt, I. (1994). Eco-tourism or ego-tourism?. Race & Class, 36(1), 49-60.

Rice, B. (2005). Seeing the World with Aboriginal Eyes. Winnipeg: University of

Manitoba.

Zapf, M. (2009). Social Work and the Environment. Understanding People and Place.

Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.