The historical significance of the Arab Spring is undeniable. It marks the thawing of the icy authoritarianism that has gripped the Middle East since the end of World War II. Many questions have been raised regarding the unique social media strategies used by citizens to bring down more than half a century of dictatorial rule.

The Arab Spring’s unique use of social media to garner political and social change has caused experts to wonder whether there should be universal Internet access worldwide. Indeed, a report filed by the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur declared that the Internet had “become an indispensable tool for realizing a range of human rights.”

The people of Tunisia and Egypt, who have recently celebrated the one-year ousting of their respective dictators, could agree with such a statement. But what about those who still live in fear under the tyranny they tried to overthrow?

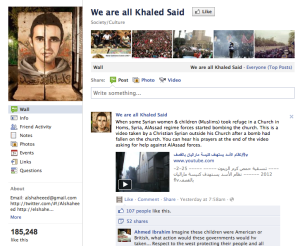

On June 6, 2010, Khalid Said, a young Alexandrian man, was dragged out of an Internet café by police officers and subsequently beaten to death in broad daylight. Pictures of his battered corpse surfaced all over the web, provoking waves of public outrage and disgust over police predation in Egypt. Eight months later, when the Arab Spring was in full swing, his death became a rallying point for the Egyptian opposition. The Facebook Page “We are all Khalid Said” obtained more than 100,000 “likes” and provided a virtual platform for activists to coordinate rallies and protests like the infamous “Day of Rage” on Jan. 25, 2011, when more than 100,000 people assembled in Cairo’s Tahrir Square to demand the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak, who had reigned for 30 years.

The revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt provide many insights into this new world of virtual activism. Given the constraints on freedom of speech and assembly instituted by both Mubarak regimes and the Ben Ali regime in Tunisia, anti-government protesters were forced to look beyond the usual means of physical mobilization and turned to the Internet for support.

Vinton G. Cerf, Google’s vice president and chief Internet evangelist, has said that the Internet “has introduced an enormously accessible and egalitarian platform for creating, sharing and obtaining information on a global scale.” By utilizing social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter, the anti-government opposition was able to disseminate information to anyone instantaneously.

Just as important was the sense of momentum and inspiration Facebook provided for the Egyptian and Tunisia youth. Facebook events gave activists a precise vision of the number of people planning to attend rallies and demonstrations. Over 95,000 people responded on Facebook to attend the Jan. 25, 2011 “Day of Rage.” “When so many respond to a social networking site that they intend to physically participate in an event, others are inspired to join, knowing that they will not be alone,” wrote Dr. Natana De-Long-Bas, a professor of Middle Eastern Studies at Boston University, in an article titled “The New Social Media and the Arab Spring.”

Current advocates for universal Internet access point to the successful cases of the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions. However, it is important to mention that many autocratic regimes have managed to hold onto power. In fact, the situations of Syria, Yemen and Bahrain seem to contradict the notion that Internet access is an invaluable tool for securing human rights.

In Bahrain, the Sunni-Minority lead monarchy responded to the Feb. 11, 2011 protest in Pearl Roundabout by creating a modern-day witch hunt on Facebook. Pages like “Together to unmask the Shi’ite traitors” called on Bahrainis to identify their countrymen for arrest. Pictures taken at Pearl Roundabout were posted on the group’s wall and users were told to write the “traitor’s name and work place and let the government take care of the rest.” Virtual lynch-mob pages began appearing as well. One page focused on a 24-year-old girl named Ayat Al Qurmezi, who had read a poem criticizing the king at Pearl Roundabout. Users posted comments like, “The people want the death of Ayat.” Shortly afterwards, she was arrested by state police and reappeared three months later on state television to issue an apology that, according to Al Jazeera, had been induced by electric shock.

The Facebook phenomenon of Khalid Said and Ayat Al Qurmezi represent two opposing outcomes. In Egypt and Tunisia, social media networks helped forge a common sense of purpose and determination that eventually lead to the fall of abusive dictatorships. In less successful revolutions such as Bahrain’s, however, Facebook and Twitter were used as tools to further infringe upon citizens’ human rights.

The Arab Spring is far from over. Although Tunisia and Egypt have celebrated their revolutions’ anniversary, many countries are still fighting for a democratic future. Social media has proven itself a valuable means to an end. Only time will tell whether that end is for better or for worse.